“We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, ... provide for the common defense .. and secure the blessings of liberty ... do hereby ordain and establish this Constitution ...”

Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, 1787

“A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Amendment II to the U.S. Constitution, 1791

As I write, El Paso and Dayton and Midland-Odessa mourn.

A nation grieves with them. And again the debate surfaces: How can gun violence be curbed and liberties preserved?

What does this contested Second Amendment really mean, anyway?

For citizens jealous of their constitutional rights, the language could not be clearer: The right to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

For citizens fearful that they or their children may be next, the disconnect could not be starker: Can’t we “infringe” something that will make mass shootings less easy to pull off?

Forgotten in the polarized arguments is the framing clause of the Amendment: “A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State . . . .”

The independence of the United States was won on the battlefield by a dual military system: a Continental Army serving “for the duration,” and short-term militia forces from the states augmenting, at strategic moments, the Continentals.

Through transformations that make it almost unrecognizable today, this system of a national army plus state militias has endured — often misunderstood, often contested, often plagued by an ambivalence that was there from the beginning. Yet always indispensable.

And somehow always related to the right to own firearms. So on this Constitution Day 2019, we ponder: How did the original Constitution of 1787 and the follow-on Second Amendment “provide for the common defense” by mandating a dual system? What is a “militia”? And what is a “well-regulated” militia?

That is, to inform today’s conversation about “the right to bear arms,” this historical analysis explains the original meaning of the Second Amendment’s often-overlooked militia clause.

Constitution: A Dual System “For the Common Defense”

Even before the Revolution, the British colonies boasted militias (which they cherished) that occasionally fought alongside British Regulars (whom they despised). The Constitution of the United States enshrined the structure of the Revolution’s hybrid army — because of a pressing question and practical compromise.

With independence won, a fearsome conundrum faced the Founding Fathers: How could the blessings of liberty be secured for successor generations? Republics, history taught, were especially vulnerable to predatory powers. Yet permanent armies, republican ideology insisted, were likely instruments of tyranny.

Security could not come through consolidated central power, for that was precisely what had triggered the rebellion. Nor could it be left to an undisciplined and fractious citizenry, easily corrupted by demagoguery. Liberty, supported by civic virtue, must find a balance between too much government power, tending to tyranny, and too little, tending to anarchy. Many leaders were forced to concede that coercive instruments of state power, including armies and navies, were needed to preserve their hard-won liberties. To form a more perfect union, capable of defending itself, required a more perfect charter of national government.

The Federal Constitution, creating a central government empowered to rule yet constrained by checks and balances, was the answer. From its precisely crafted language sprang the strategies and forces to defend a nation that within six decades would stretch to the Pacific.

Some of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention — label them “nationalists” — dreamed of a truly United States, with a central government strong enough to serve its citizens while protecting against foreign threats. They feared that the new republic might dissolve into competing localities. Others (call them “localists”) remembered British tyranny and feared the opposite: that a powerful central authority would erase state power and destroy individual liberty. The nationalists wanted a unitary national military; the localists sought to assign military power to state militias.

To understand the framers’ conflicted psychology, try this thought experiment. Imagine an old playground seesaw. Lots of little kids bunch on one side; a few fifth graders at the other end keep it in balance. The many stand for the mass of people; the few represent the weight of government authority.

The perfect balance between the few and the many, the government and the people, equals true liberty — each keeping the other in balance. But if too many eager kindergartners jump on, the seesaw tilts. Too much power in the hands of the people corrupts liberty into anarchy. On the other hand, one more big kid could launch the little ones to scary heights, illustrating that too much centralized power threatens the opposite enemy of liberty: tyranny.

Oppression’s chief instrument — its overweighted and abusive bully — was a “standing army.” The militia offered an alternative. But to prevent the anarchy of the undisciplined many, it had to be a well-regulated militia. That was “the only form of defense compatible with liberty,” as historian Saul Cornell puts it.

Thus the Constitution divided responsibility for defense among branches of the central government and between the national authority and the states. The president was designated commander-in-chief, including over state militias when in federal service. But any federal force (standing army) must be raised, funded, and managed by Congress, which had the sole power to declare war. Congress further held significant authority over state militias, charged with “organizing, arming and disciplining” them and “governing” them when in federal service. Offsetting that grant of centralized power was the provision that the states retained the right to appoint officers and train their soldiers.

In sum, the Constitution codified a dual system of national forces and state militias, sustaining the Revolutionary War pattern. Central to the system was that the militia must be “well regulated” by the national government.

No one doubted that the militia should endure: It was a longstanding and well understood fixture of American social order.

Militia: An Ancient Institution

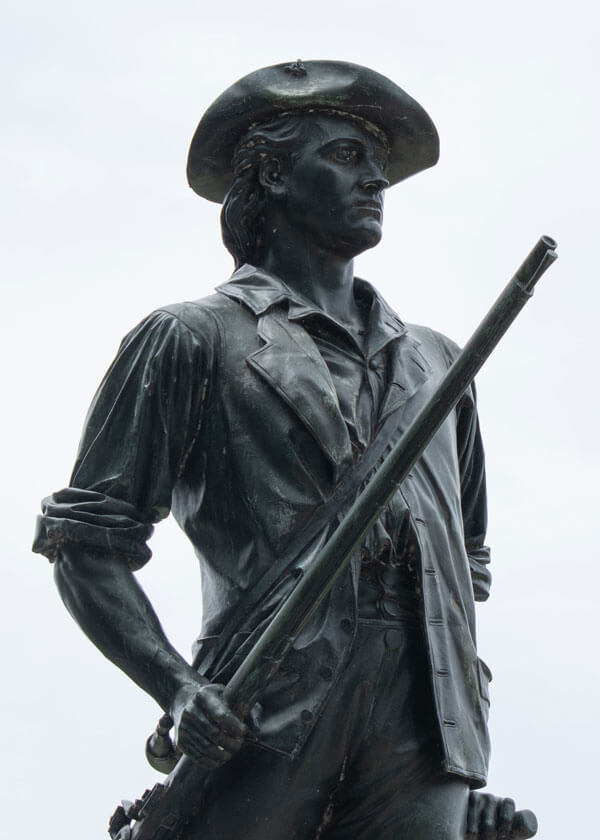

It is a quiet town. The narrow roads dip and bend, veer and halt, in random pattern and jerky dignity. Yet this old Massachusetts village of Concord is also, for thousands of American pilgrims, a destination. For there stands the Old North Bridge, and before it one of the most powerful icons in the land.

The bronzed farmer has that look typical of all heroic statuary as he grasps his plow and shoulders his musket. Tourists recite the inscription below: “By the rude bridge that spanned the flood,” they murmur. “Here the embattled farmers stood/And fired the shot heard ’round the world."

The Minuteman! Mythology and history, nationality and nostalgia, patriotism and parody — all engulf this monument. It hymns the militiaman, the citizen-soldier, productive in peace, ready in crisis, invincible in battle, eager to return to family and farm when victory is won. He earned his immortal station on an afternoon in 1775; he lives on in hallowed bronze, the selfless American hero.

But what of the unalloyed fact underneath the encrusted myth? What is the militia, really?

A state militia is a formal organization of citizens taking up arms in military formation to defend their homeland. It is constituted by, and subordinate to, local and state government.

It holds an ancient pedigree, perpetuated in all the North American colonies, Spanish and French as well as English. As the familiar story rightly has it, in the 1770s the Massachusetts government, in defiance of British efforts to disband militia formations, designated a few companies to be so trained and armed that they could spring to community defense at a minute’s notice. When the warning came that Redcoats were marching to Concord, they sprang to their muskets. These were the “minutemen” of iconography and lore.

The American militia began in glory, but also in disgrace. They may have fired the first shot, but they did not win the war. The army that did was the permanent Continental Army. Himself a militia colonel, General George Washington bemoaned the militia’s failures of discipline and reliability. He pressed Congress that “no dependence be put in a militia.” When militiamen fled from the Manhattan battlefield in 1776, Washington exploded: “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?”

Yet the Continental Army could not have won the war without the militia companies that valiantly defended their own home counties. Even Washington at war’s end conceded as much. If the militia’s performance was abysmal, it was also essential. It could be a sound foundation for the future, Washington believed, if properly trained.

And therein lies the key to the origins of the Second Amendment.

Caveat: A Well-Regulated Militia

Firm in the memory of Americans after the Revolution was a fearsome double affront from the British. Beginning in Boston in 1768, British Redcoats were stationed in American towns, far from the frontier where they might protect against native tribes. Here in scarlet was an abhorrent standing army. Then, in 1775, the British tried to destroy the militia’s stockpile of powder and stores. That’s what provoked the clash at Concord Bridge: an attempt by a standing army to disarm the citizenry.

A Boston petition voiced the horror: Americans had a right to “have Arms for their Defenses,” in keeping with “wholesome” colonial militia laws. Those laws in turn rested on the English Bill of Rights of 1689, which, as codified by the great English jurist William Blackstone, was a political right of the people on a par with rights of assembly and petition. Indeed, participation in one’s local militia was an obligation. Militia laws required citizens to own a musket to bring to mandatory militia musters. A free people accepted the right and duty to rally to their own defense; “a well-regulated militia,” concludes Cornell, “was central to their way of life.” In sum: “Citizens had both a right and an obligation to arm themselves so that they might participate in a militia.”

These views became a repeated refrain. Many of the new state-level constitutions explicitly asserted a right to bear arms “as a civic obligation.” Virginia’s early and influential Declaration of Rights affirmed that “a well regulated militia . . . is the proper, natural, and safe defence [sic] of a free state” but must always “be under strict subordination to” the constituted government. The Massachusetts Constitution similarly proclaimed that the “People have a right to keep and bear arms for the common defence [sic].”

When these states enacted militia statutes, they detailed strict requirements for citizens, not only to own firearms but also to report that they did so. If they failed to show up for a muster they faced fines!

In a 1783 paper titled “Sentiments on a Peace Establishment,” George Washington himself provided perhaps the best idea for how the state militias could become the bulwark of national defense. He agreed that “a large standing Army in times of Peace hath ever been considered dangerous.” But he did not shrink from the pragmatic reality that the infant republic faced grave perils. To preserve a secure peace required preparing for a future war. To use 20th century language, the general envisioned a strategy of deterrence resting on a trained militia ready to fight if deterrence failed. The new republic’s army should therefore combine, he argued, “a regular and standing force” with a backup “Continental Militia” held to a carefully prescribed training regimen for citizens “ever ready and zealous to be employed” in their country’s defense. Such a “well regulated and disciplined Militia” was the best means to “preserve, for a long time to come, the happiness, dignity and Independence of our country.”

The Constitution of 1787 incorporated this “dual system” by which Washington had won the war and now envisioned securing the peace. Then came the Bill of Rights.

In the First Congress, James Madison resumed his role of constitutional architect, boiling down a basket of proposed amendments. In the process, a significant and intentional phrasing of the future Second Amendment was adopted. The purpose of the specified right to keep and bear arms was placed at the beginning, to show its civic context. (Such “preambles” to legal stipulations were familiar ways to clarify and constrain what followed.) This clearly signaled that the purpose of the amendment was to sustain the militia as an armed state force.

This point cannot be overlooked. The Amendment’s single compelling rationale was to preserve the state militias. It had nothing to do with individual self-defense.

The language of the Second Amendment, then, was a completely transparent and commonly held phrasing that encoded the longstanding commitment to citizen soldiers under the control of civil authority: a well-regulated militia.

And those soldiers would be trained and deployed on the cheap. As part of their civic duty, they would have to buy their own weapons.

Threats: “Enemies Foreign and Domestic”

The militia, says the Amendment’s final text, was essential to the “security of a free state.” But what, at the nation’s founding, threatened the republic, thus necessitating a well-regulated militia?

Washington’s “Sentiments” had recognized both external and internal perils confronting a young and weak new republic. First were the bordering nations, or rather their territories: Britain to the north (refusing to fully evacuate from U.S. soil), Spain to the west and south (eventually France in Louisiana). Their respective kings were locked in endemic conflict with each other, and ill disposed toward an upstart republic that condemned monarchies. Next were the hostile tribes in the interior, justly angered by American incursions, justly suspected of being armed and incited by British agents. Then there were potential internal insurrections. A few had already erupted; southern states explicitly dreaded slave uprisings.

More subtly still, the economy was in shambles. Only a strong central government could raise revenue and regulate commerce. Only an effective armed force could protect merchant ships and coastal towns.

Yes, permanent standing armies could be corrupted into instruments of tyranny. But without a strong military to defend against such imminent threats, liberty could be equally imperiled.

In 1790, a well regulated militia was, indeed, necessary to the security of a free state.

Legacy: The National Guard

What has become of the militia that was so central at the founding?

In 1792 the Congress opted to, well, opt out. A very weak Militia Act dumped the responsibility on the states. All males aged 18–45 should be enrolled. But no funds were provided, so each must bring his own firearm, as the Second Amendment assumed.

The Act supposedly set up a system to provide for the common defense. It remained on the books for more than a century. In effect, in rejecting a sizable professional armed force, Americans adopted a localized form of universal military service.

It didn’t work.

The ostensibly compulsory system withered in the first half of the 19th century. Law-abiding citizens ignored the law. The state militias by mid-century were dead.

Instead, a mutant system evolved in the early 1800s: volunteer militia organizations similar to other local voluntary associations. Religious societies, fire companies, humanitarian charities, literary guilds, even the first baseball clubs — all reflected the era’s energetic spirit of collective striving for personal and social improvement. Autonomous and manned proudly by members from particular social segments, the volunteer militia companies devised rituals, designed distinctive (not to say outlandish) costumes, elected officers, and celebrated the martial virtues. Members found sociability and status, if not rigorous grounding in the skills of real soldiering.

Yet they formed the core of a national defense force when need arose. Indeed, the volunteers were the primary manpower source in the War of 1812, Mexican War, and Civil War.

But the system proved a near-disastrous failure in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Hence in 1903 a transformative new Militia Act was passed, reviving and formalizing the old dual system. The militia became the National Guard, subject to federal training protocols, paid from federal coffers, and designated a national reserve force, subject to the call of the U.S. president.

Thus World War I was fought by a new kind of American army. The American Expeditionary Force in France combined a small regular Army and National Guard organizations from the States (plus draftees). It was the first test of the Guard in its newly legislated status as both a state force and a federal reserve. And as the doughboys returned and settled into postwar life a century ago, Congress made this new-old system self-sustaining.

Several refinements have since been added, most notably the creation of an Air National Guard when the U.S. Air Force became a separate service after World War II. From then till now, from Korea to the Middle East, Guard units have mobilized for conflict, then returned to state-run duties.

And a bipolar attitude about America’s armed forces accompanies them: The Guard is a superfluous nuisance that complicates national defense policy; the Guard is a cost-efficient essential asset that constrains federal adventurism and bolsters America’s military muscle. Despite such public ambivalence, men and women of the Army and Air Guard now regularly place their “boots on the ground” both in overseas hot spots and at scenes of mudslides, wildfires, and floods right in their backyards.

The well-regulated militia has come a long way.

Right and Duty

The Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution, and Bill of Rights were all rooted in a distinct view of liberty. Again quoting Cornell, this was “not the unrestrained liberty of the state of nature, but the ideal of well-regulated liberty.” Thus the notion of an armed populace “reflected a more fundamental belief that citizenship was tied to a set of legal obligations and demanded a certain level of public virtue.”

Enshrined in the Second Amendment, then, is a great ideal. The founding generation maintained militia as “a civic right . . . to keep and bear those arms needed to meet their legal obligation to participate in a well regulated militia.” Whatever the Second Amendment right should mean today, we must not detach it from its roots in a blend of right and duty.

The 21st century descendants of the early militia soldiers, the men and women of the Army and Air National Guard, hope you realize that their service stems from that potent and patriotic combination.

William Woodward is professor emeritus of history at Seattle Pacific University. Co-author of Washington National Guard, to be released next month, he served as a Guard officer for 25 years. He specializes in the military and diplomatic history of the Pacific Northwest. This is his 15th Constitution Day contribution.